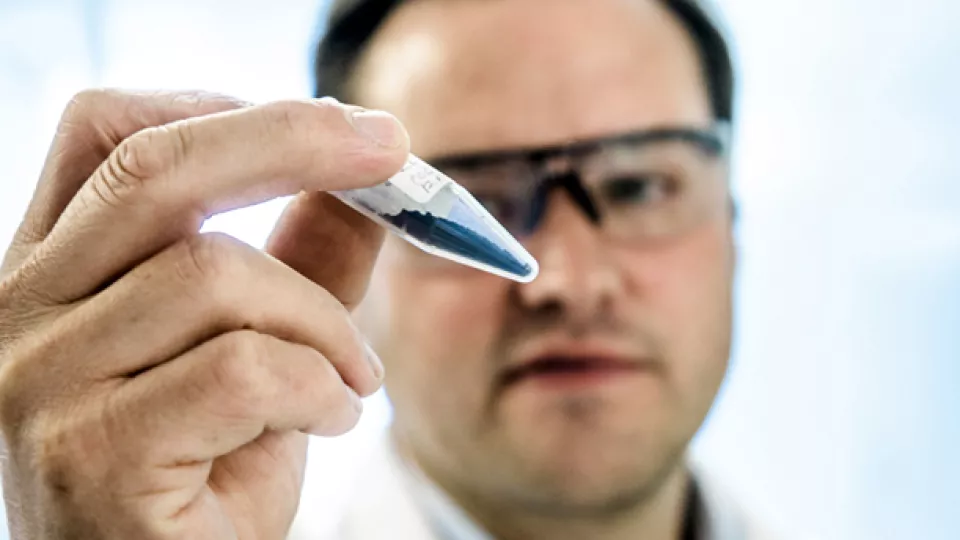

“This is extracted lignin from pine and birch, which can then be catalysed into petrol or diesel, to supplement ordinary fossil fuel alternatives”, says Christian Hulteberg while waving a small plastic container with a brown powder inside.

He is wearing a white coat and safety goggles in his lab in Tygelsjö, where several spinoff companies from the research at Kemicentrum in Lund have taken off. Lignin research has already made great strides. Full-scale manufacturing in collaboration with stakeholders is underway to convert spruce into petrol.

The great advantage of this technology, according to Christian Hulteberg, is that it fits into existing manufacturing techniques and does not require new intermediate processes.

“It’s a win-win-win situation. Forest owners will gain an additional income, the pulp industry can prevent bottlenecks, and fuel producers avoid penalties”, he says.

The latter, penalties, refers to the new quota duty currently in force in Sweden. It requires fuel suppliers to have renewable components in both petrol and diesel. The required proportion of renewable components is gradually increased with the indicative target of 50% by 2030.

Once lignin petrol is available at service stations, the amount of renewable petrol and diesel is estimated to increase from today’s approximately 300 000 tonnes per year to between two and three million tonnes per year.

Fuel made from renewable raw materials is not a new phenomenon. Plants – even the tougher parts such as twigs, sprouts and chips – can become fuels that do not increase carbon dioxide emissions.

Ethanol is by far the most widely used biofuel in the world. However, in Sweden, politicians have turned their backs on ethanol and instead the most common Swedish biofuel is biodiesel made from pine oil or fats.

“There are many ideas, but most are still more expensive than pumping raw oil from the ground, so the challenge is making them financially viable. You may also question the sustainability of some of them. Some compete with food, and certain types of biodiesel are made from palm oil, which is not so good”, Christian Hulteberg points out.

Swedish initiatives are held back by policies that are currently only aimed at increasing the use of biofuels, which often favours cheaper, foreign biofuels.

We step outside the lab and into the sunshine, trying to find a grove to represent a forest in which Christian Hulteberg can be photographed. We find some pines, and while photographer Kennet Ruona sets up his camera, I ask the rhetorical question of whether working with biofuels even makes sense now that electric cars are all the rage?

“Electrification is nowhere close to solving the problem of heavy and long transports; it would require a huge expansion of the electric grid. And half of our electricity comes from nuclear power plants. The most important thing is that we achieve green energy production. The amount needed is huge so I personally believe it requires several solutions.”

“This renewable raw material is nevertheless also needed, even if we were only to use electric cars. Today, chemicals and plastics are primarily made from fossil oil. There is a huge adjustment to be made in this area.”