Human remains in a museum context awaken many feelings. As recently as last year, Lund University handed over, or repatriated, the remains of an Aboriginal man to his home country at a ceremony at the Old Bishop’s House attended by Australia’s ambassador.

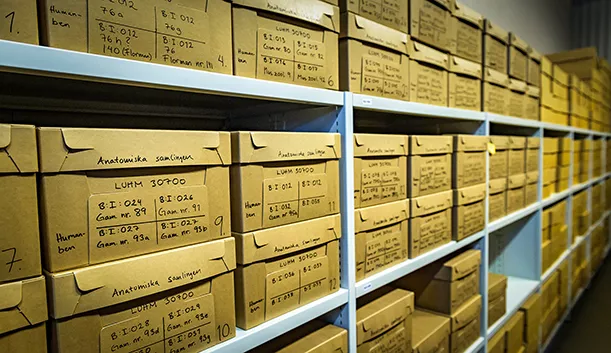

“The collection has not been reviewed properly since it was transferred here from the Department of Anatomy. Quite a lot of questions remain, and that is why it is so important that we are making this inventory. To justify that we have human remains, and to create better conditions prior to possible repatriations, we simply need to know more about the individuals in question”, says archaeologist Jenny Bergman.

“The purpose of the museum’s collections is not just to lie there gathering dust – they are to be used. The anatomical collection is partly a result of a dark chapter in the history of Sweden and the University, but that doesn’t make it any less important to preserve. Concealing it would be historical revisionism”, says Jenny Bergman.

Searching for life stories

The collection contains some 20 named individuals from the 1800s.

“We are trying to find out as much information about them as possible through searching in archives at the University and in the region, in medical case records and in prison archives. What is apparent is that it concerns vulnerable people. The laws of those times determined who was sent to the dissecting room. As suicide was stigmatised and only decriminalised in 1864, those who took their own lives ended up here instead of being buried at once, and some of them remained at the Department of Anatomy. Others died from diseases, mainly TB. One was executed in 1817 for the murder of a guard. Some died in custody. Farmhands, hunters, a soldier. Most were men, but the remains of a maid and two female servants are also named.

“Each one of these individuals has a story to tell. And even though they are upsetting stories, they need to be heard. It feels good to be able to give a voice to ordinary people, to those other than kings and noblemen. This was one of the main reasons why I was attracted to human osteology – that you actually get close to these people, even though it is in a different way”, says Maria Petersen, archaeologist and human osteologist.

Possible to find out a lot – also about medieval lives

Most of the remains are not from the 1800s, but from the Middle Ages or earlier. However, it is also possible to find out a lot about them regarding living conditions using osteological analyses. They have been found during archaeological excavations.

“What did they eat? Were they malnourished? Did they have deficiency diseases? For example, by measuring thigh bones we can get a picture of their height and that is linked to health: the better the nutrition, the better the conditions are for the individual to be taller. We can also take strontium samples to find out where they were born and lived for the first few years of their lives”, says Maria Petersen.

Concealing or being ashamed of the collection, is something we have to put an end to. Instead, we are placing our cards on the table

Using ultraviolet torches to find inscriptions, visiting archives and registries, exercising patience and repacking carefully, Jenny Bergman is going box-by-box through the shelves of the museum’s storage facility. Together with osteologist Maria Petersen and conservator Maria Jensen, she is carrying out the extensive inventory. It concerns bringing order to the collections and with self-examination, humility and respect working through a dark chapter in the University’s history.

“Concealing or being ashamed of the collection, how it has been acquired and what it contains is something we have to put an end to. Instead, we are placing our cards on the table”, says Jenny Bergman.

However, the work takes time and requires resources, which currently are not available. For that reason, the museum is applying for funding to enable the completion of the extensive work.

“In the best of all possible worlds, we would already have secured funding to do this”, concludes Maria Petersen.