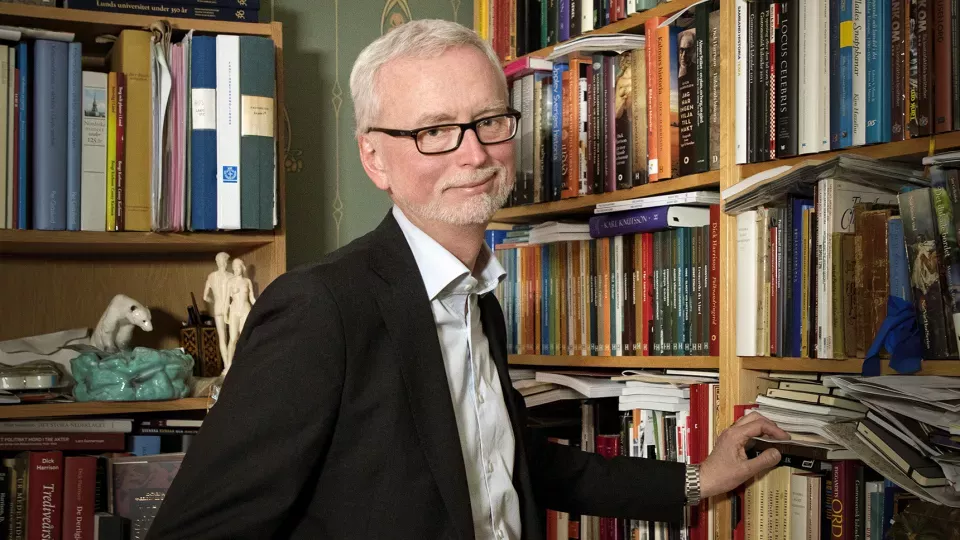

It’s winter and muddy on the drive in front of the Harrisons’ Art Nouveau villa in Åkarp. One end of the house is a building site. In a few months’ time, the new library will be finished. Two floors with large panes of glass, a fireplace and ceilings seven and a half metres tall. There will be room for more than just books.

“My wife and I have perhaps the largest collection of Christmas baubles in Sweden, so of course we’re going to have a really big tree in the library when Christmas comes,” he says, pointing into the study where 104 of his books are lined up, taking up three and a half shelves. The 105th, a mystery novel called Herrens år 1402 (In the Year of the Lord 1402), was published a few days before LUM was sent to print.

Dick Harrison is well aware that his name is a brand. He is probably Lund University’s most famous public figure. At least at home in Sweden. More unexpected is his success in the Netherlands, where his non-fiction books have sold over 50,000 copies.

Twice a year, he notices his celebrity during the Gothenburg Book Fair and Medieval Week on Gotland. The latter is a kind of holiday from reality as he spends a week in August walking around Visby in strange clothes.

The name of the game

“That’s when I feel a bit like an academic Bruce Springsteen. I treat myself because it’s fun and I get a kick out of it, and sometimes people ask for my autograph. But otherwise, I don’t feel like a celebrity. It’s not like I get stopped at ICA.”

Dick Harrison does not take his job lightly. Hard work is the name of the game, every day. He gets up at 4:30 am, gets ready, works for a couple of hours and then prepares breakfast for his wife and daughter. Then, more work, all day long. He is often found teaching, otherwise doing research and writing. He doesn’t need breaks or bother with fika. Lunch is also a rarity.

“I’ll eat some fruit, that’s enough. I love my work and I use every minute I have. Unless a student catches me between two lectures, I work. It’s my life. I work very hard and write every spare moment I get.”

Wrote for a living

There’s no mistaking the efficiency and incredible productivity. The explanation for his flow and lack of writer’s block is the Swedish National Encyclopaedia (NE). As a newly minted PhD at the age of 21, he was recruited to write for the NE. He is not boasting when he says:

“I wrote for a living, and I wrote anything and everything the Swedish National Encyclopaedia asked for. When the professors started to tire around the letters i, j and k, I took those on too. I became one of the most diligent and productive writers they had.”

After that, he moved on to another reference classic, Bra Böcker’s Lexicon 2000, where he wrote all the history. In total, it represents more than ten years of daily work producing succinct, concentrated texts. Almost always with a deadline the next day.

“That was how I learnt my craft and how to overcome writer’s block. I write fast, but research takes as long for me as anyone else.”

Writing books and doing research is fun, but after talking to Dick Harrisson for a while, you understand that teaching is what excites him the most.

“Teaching at university level is my calling, though, the thing closest to my identity. I genuinely enjoy teaching and it is no coincidence that I frequently lecture outside Lund University in my spare time.”

“grey zone of popular history”

His writing career, however, happened more by chance. Popular history writing was an obscure endeavour when the publisher Prisma first contacted Dick Harrison. When other publishers followed suit, he realised that he had found a second profession. And one that could be developed in parallel with his work at the University.

Yet he was afraid to take the plunge and write in what he calls the “grey zone of popular history”, that is, until he got his first permanent position as senior lecturer in Linköping in the mid-1990s.

“There was a taboo around writing for a popular audience at that time. It was not something an academic did. It worked against you, even. I’ve been an external expert for appointments and I know how the talk went.”

“Today it’s not a problem at all, and it’s part of my job. Research is one part, as is writing. The fact that people want to read what I write is just a bonus.”

Podcasting with his wife

Dick Harrison is careful when describing his writing. He writes non-fiction as part of his job. The fiction writing, including the crime and mystery novels, is done as part of a separate company, and that is in his leisure time. When he is hired as a consultant or adviser, or gives talks outside the University, it is also within the framework of his company.

The same goes for the podcast Harrisons dramatiska historia (Harrison’s Dramatic Histories), which he and his wife Katarina Harrison Lindbergh produce together. It has grown quickly.

“We started the podcast just over a year ago and are already recording season five.”

He regularly receives offers and requests. He says no to many things, the reason being a lack of time. Daytime television sofas have fallen by the wayside. The same goes for entertainment shows in which he feels producers want him to play the funny professor.

“There have been a few such offers and at one point Lund University even tried to pressure me to accept, but I said no.”

Success comes at a price

His last TV appearance was in a Christmas edition of Kulturfrågan Kontrapunkt on SVT. He is also one of the experts behind SVT’s lavish flagship series the History of Sweden. He is happy to do his part in the name of popular history but prefers to have some control over how he is portrayed.

“It has gone wrong a few times and that makes me cross.”

What has bothered you?

“When my words have been twisted. People wanting to have an academic alibi but not really caring what it was I was saying.”

Success and fame come at a price. In the debate about immigration, he takes a positive view, resulting in threats that had to be reported to the police. Inside the university world, he has come face-to-face with academic resentment.

“I’m often ignored, and people try to make me invisible. They pretend I haven’t written books on a certain subject and don’t invite me to conferences. It’s the academic way of showing jealousy,” he says and continues:

“I strongly dislike that kind of academic stinginess and pettiness, but I have spent almost 40 years studying history every day and I never get tired of it. Teaching is as much fun now as when I started.”