Peter Svensson wrote the book, “På engelska förstår jag ungefär” (I get the gist in English) together with Ola Håkansson, a publisher at Studentlitteratur. The book is both a contribution to the debate and a review of research on English as a language of instruction in Swedish higher education. The authors themselves conducted a survey using open questions and garnered more than 30 responses from university teaching staff.

“The answers are very detailed. They deal with the frustration of not reaching students, being tied to scripts and using ‘juvenile language’. You end up with more lecturing and less interaction,” says Peter Svensson.

Risk of inferior learning

They also refer to several previous studies that unequivocally show that “learning in a foreign language is associated with poorer academic performance in universities’ first and second-cycle programmes” and “those who were taught in their mother tongue, Swedish, learned much more than students who took the course in English.”

“We wanted to write the book because we find this development so annoying. Since the Bologna process, we see an anglification of Swedish education, mixed with internationalisation, the downside of which is that students might understand half of what is said. This leads to instrumental, inferior learning,” says Ola Håkansson.

“Many teaching staff are also less proficient in English than students. But the students speak a different kind of English – they know the language and jargon of online games,” says Mr Svensson, adding:

“There is an overconfidence among Swedes themselves. ‘Swedes are good at English,’ they say. That, however, is a myth.”

Since his doctoral thesis 20 years ago, Peter Svensson has studied the use of language in public relations agencies, in annual reports and at annual general meetings. The field is Critical Management Studies. At the School of Economics and Management, he teaches qualitative methods and marketing, among other things. For the past two years, he has taught the course “The Darkness of Business”, which the faculty offers under the “Winter School” concept. It brings students from partner universities of the School of Economics and Management and the Hanken School of Economics in Finland to Lund and Helsinki for two weeks of intensive study.

A slower learning process

“Of course, I teach in English then, as none of the participants are from Sweden. Of course we should be able to use English as the language of instruction – when necessary. That's our point, that we currently do it almost all the time without reflecting on the purpose of doing so,” says Peter Svensson.

He adds that when he teaches in English, to students who are also non-native English speakers, the process is a bit slower.

“I'm careful to check with the students: are you with me?”

Peter Svensson and Ola Håkansson have seen their careers take similar paths, Peter as a university lecturer and Ola as a publisher of academic literature.

“Ninety-three per cent of all theses defended in Sweden today are written in English. This was not the case 20 or 30 years ago,” says Ola Håkansson.

In 1979, the corresponding proportion was 75 per cent. In the humanities, the figure was 27 per cent, for social sciences just over 30. By 2019, it had risen to 70 and 75 per cent respectively.

Several dangers

Both men see several dangers in the dominance of English over Swedish in today's university world. They speak passionately, sometimes almost over each other, listing a string of arguments. It is clear that they really care. Ola Håkansson:

“Have we forgotten that according to the Language Act, Swedish is the official language of public life in Sweden? Lund University is a public authority. That being the case, how can courses and information be provided only in English? It is not just about the student's lack of learning. It is a work environment problem, an education problem, a democracy problem – and a class issue.”

Peter Svensson adds:

“How can we accept the loss of domain that comes with losing the Swedish technical terms? Shouldn't we be able to talk politics or business in Swedish?” he asks.

Isn’t there a point to learning business terms in English? Surely this is something that students will benefit from in working life?

“Yes, certainly, but at the expense of what? The price of a “business jargon” is the understanding behind it,” Peter Svensson instantly replies. He continues:

“Students may be able to talk, but do they understand what they are saying? Instead of learning the subject in depth, they have to spend time decoding English concepts. They learn less and have a shallower understanding than if they had been able to receive both teaching time and literature in Swedish.”

English at master's level

He firmly believes that first-cycle teaching at Swedish universities should be conducted largely in Swedish, in order to prioritise the learning of Swedish-speaking students.

“Universities are by definition international, we need a Lingua Franca. But not in the first-cycle. At Master's level and above, there is a point to teaching in English. By then, you already have the basic knowledge,” says Peter Svensson.

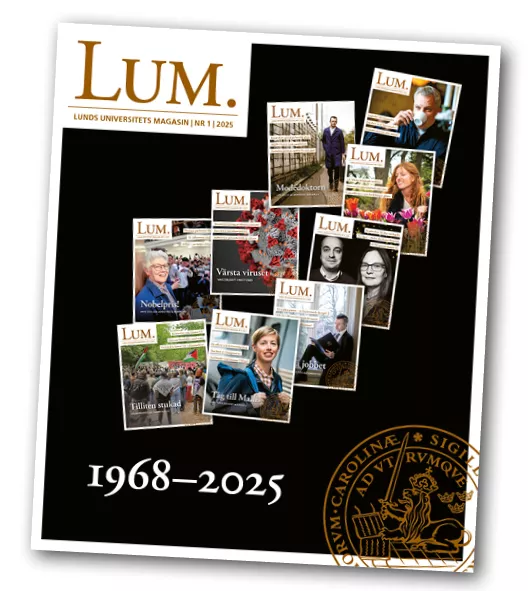

What is your main message for the readers of LUM?

They briefly fall silent. Then Peter Svensson says:

“We have detected a kind of fatalistic resignation, both in our survey and when talking to colleagues. Most people agree with us, but it's like “this is the way it is”. It is a bit provocative: Who are the people sitting on faculty and university boards? Who is it that decides on the language of instruction and course literature? It is us of course! The beauty of academia is that it is led collegiately. It ought to be possible to do something. If the will is there.”

“But you are romanticising a bit now," Ola replies.

“Academic leadership is for amateurs, in a positive sense. Maybe it just needs a rethink. For us to say that language management is to be a strategic issue at universities. Then it can trickle down through the organisation,” says Peter.

“We are not saying that nothing should be in English. Just that it should be a strategic decision – every time,” says Ola.