There is a smacking sound as Fredrik Terfelt pulls on the thick rubber gloves and opens the door of the fume cupboard. He takes a deep breath in his gas mask and grips the bottle of concentrated hydrofluoric acid that is to be poured into the plastic beaker of sediment. A steady hand is needed. Just a few drops of hydrofluoric acid directly on the skin is enough for the toxic substance to infiltrate the body and wipe out the nervous system. However, Fredrik Terfelt does not dwell on this as he carefully pours the acid over the muddy mixture in the beaker.

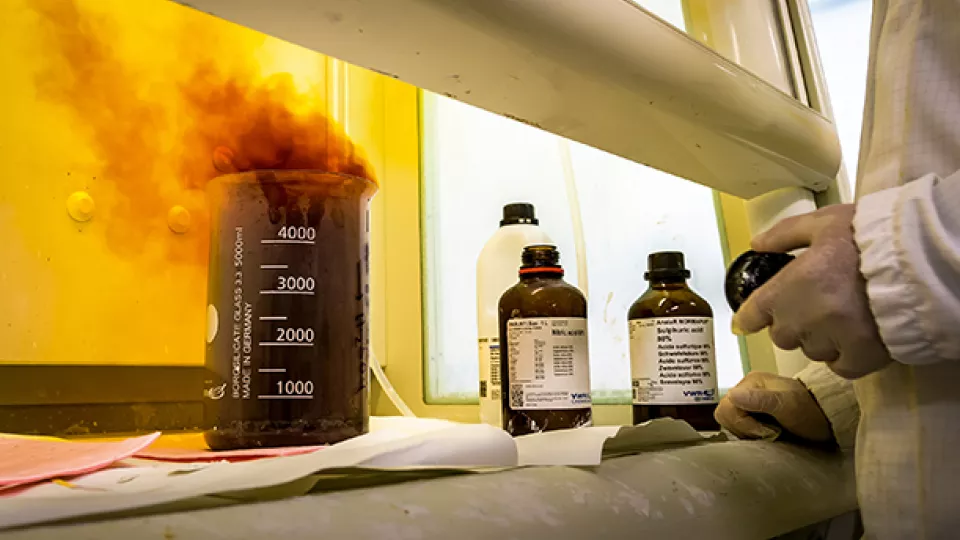

At one point, he pours concentrated nitric acid on a sample with large amounts of the mineral pyrite. Thick, brownish yellow smoke rises up out of the glass beaker and Fredrik Terfelt takes a step back.

"You could say our work is based on trying to find a needle in a haystack, but we do it in a special way, namely by burning down the entire haystack", he says, smiling behind his gas mask.

Fredrik Terfelt is a research engineer and manager at the Astrogeobiology Laboratory based at Medicon Village in Lund. Together with his research group led by geology professor Birger Schmitz, he travels the world collecting million-year old limestone samples. In the sediment, there are small, barely visible meteorite grains that have fossilised and become embedded in the sediment. By analysing these extra-terrestrial chromite grains, Fredrik Terfelt and his colleagues can gain important knowledge of how events in space have impacted life on Earth over the course of millions of years.

Recently, the research group was able to establish that a gigantic asteroid collision 466 million years ago contributed to an ice age that led to the development of climate zones. In turn, these contributed to a dramatic increase in species richness in the animal world. The material studied by the researchers was fossilised meteorite grains from a quarry in Hällekis on Mount Kinnekulle – a place that, at the time of the asteroid collision, lay on the ocean floor south of the equator, a few hundred metres below sea level.

"We call our research field astrogeobiology. You could say that we work with astronomy, but instead of looking out into space, we look down into the earth", says Birger Schmitz.

After yet another invigorating bath in concentrated sulphuric acid and one round in the specially designed shaking machines, doctoral student Ellinor Martin sifts out the chromite grains of extra-terrestrial origin, which are barely visible to the naked eye. Since 2013, the researchers have dissolved approximately 30 tonnes of limestone. The result: a few thousand extra-terrestrial chromite grains with a combined weight of approximately one hundredth of a gram.

"We study grains of 32 to 35 micrometres under a scanning electron microscope that are then sent away for analysis to world-leading cosmochemical laboratories. In the chemical composition of the grain there are clues to how events in the universe have impacted life on Earth", says Ellinor Martin.

She is currently working on the Tycho crater on the south pole of the moon, which formed approximately 110 million years ago. Ellinor Martin is trying to find titanium-rich chromite grains on Earth that originate from the large asteroid collision with the moon.

"However, it is hard to know in which deposits to look since there is an uncertainty factor of several million years. There are staggering timeframes to consider."

Fredrik Terfelt is absorbed behind the scanning electron microscope. Ellinor Martin continues to sift out interesting grains. In the laboratory, Italian limestone is simmering in hydrochloric acid and hydrofluoric acid. Perhaps the new extra-terrestrial chromite grains waiting to be discovered could lead to an increased understanding of how the galactic year – the 225 to 250 million years it takes for the sun to complete a lap around the centre of the Milky Way – could be linked to the history of life and of Earth. At least, that is what Birger Schmitz, Fredrik Terfelt and Ellinor Martin hope to discover.

"This is like assembling a really big puzzle with not nearly enough pieces. We do not know if the picture is going to be a Picasso or a Leonardo da Vinci. But that is exactly what makes this job so exciting", says Birger Schmitz.