Robots pique the imagination and society’s expectations have been heightened by the media. It is not always easy for researchers to resist and sometimes reporting is exaggerated. The same thing may happen when applying for grants.

“It’s a case of really wanting to appear to have progressed a lot further than the last time you applied for funding… “

There is also a rush to publish due to the nature of the qualification system. And there is a tendency to exaggerate the significance of their research results, comments Christian Balkenius.

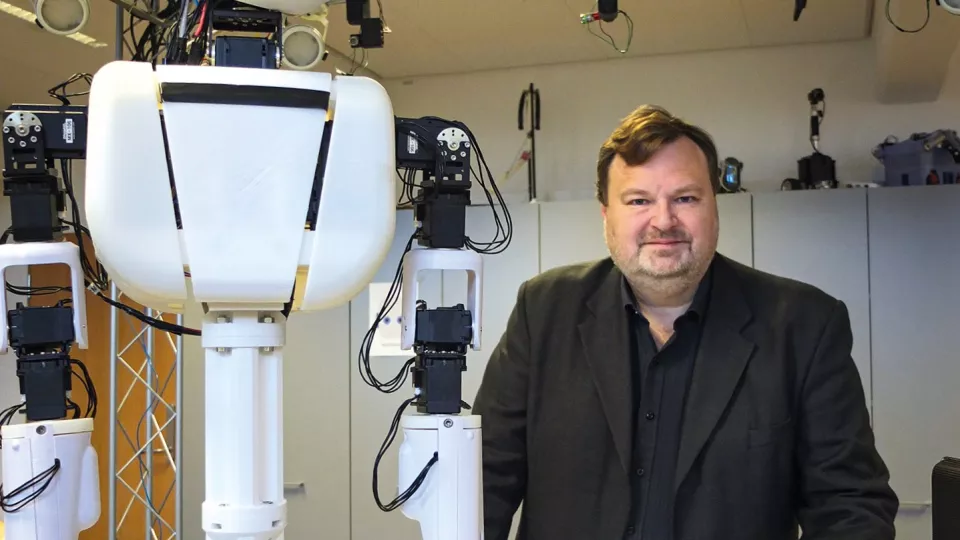

He is Professor of Cognitive Science and Director of the graduate school in the WASP-HS research programme (Wallenberg AI Autonomous Systems and Software Programme – Humanities and Society) which will engage 70 doctoral students throughout Sweden in due course.

He is a central figure for the biggest investment ever in the humanities and social sciences in Sweden. At present, the funding of SEK 660 million covers 16 research projects (three of which are in Lund) and the graduate school. The unifying theme is how artificial intelligence is going to affect people. The Wallenberg Foundations are providing the funding and that has a special significance according to Christian Balkenius.

“They have funded a lot of the AI research in Sweden and therefore it’s pleasing that that they now want to fund something that is about the consequences”, he says.

So, where does robot research stand – will the robots take over and become smarter than us?

“No, no, not in my lifetime in any case. We are only at the beginning of this development”, reassures Christian Balkenius.

That does not mean, however, that technological development is standing still. On the contrary, there is a lot happening and relatively fast. However, there is a long way to go before a robot can reach a human level.

“Nowadays, a robot can function in a factory or in a spacious warehouse – or in a large office with no carpets or thresholds. They can move paper and things from one place to another.”

Christian Balkenius has a couple of robots at home, but he is only content with the robot lawnmower. The robot vacuum cleaner is not doing a very good job…

“A lot of intelligence is required to function in a home.”

What about robots as company for the elderly? He immediately dismisses this as a bad idea. However, he sees a strong future for robots in assisting the elderly who want to remain in their own homes, and in elderly care as a whole.

A friendly face is important for a robot

The smiling robot face that greets visitors to the lab at LUX, where Christian Balkenius and his colleagues work, is for research, in this case basic research. The researcher’s everyday work here is devoted to his own project “Ethical aspects of autonomous AI systems”, which he hopes will pave the way for empathic robots.

“We have started by giving them a friendly face!”

That seems a lot easier than giving them a good heart. Christian Balkenius talks about the jungle of rules that exist for how people are to act and behave in various situations.

“But robots can interpret rules in different ways and it’s not at all certain that the results will be the ones you intended”, he says.

Morality is not an altogether easy aspect either. He points to the example of self-driving cars.

“If a crisis situation arises in traffic, the car must decide who to save – the two in the street or the person driving the car?”

Christian Balkenius tests various ethical theories on the robots and observes how they work in practice. One theory may concern duty – doing the right thing – and another on doing good. There can be a lot of ethical dilemmas.

Research involves helping robots to try to understand how people are and how they feel

The development of artificial intelligence has come so far that it is impossible to slow it down and Christian Balkenius therefore considers that the best possible outcomes must be pursued in this situation. Asia, and Japan in particular, has established a slight lead, but now – thanks to major EU projects – Europe is in the process of catching up. There are, however, a number of cultural differences regarding views on when and how robots should be used. For example, nations such as Japan and USA are responding differently to the growing care needs of an aging population.

“For the Japanese, solving the problem with robots is the natural path, whereas in the USA cheap labour is used instead.”

As Christian Balkenius and his research colleagues’ work involves helping robots to try to understand how people are and how they feel, they learn a lot themselves about people’s behaviour in different situations.

“For example, what is the acceptable distance when you stand next to another person so that it feels comfortable? And how do you adapt to different groups and sense social norms?”

It is clear that the development of empathic robots requires many disciplines, and Christian Balkenius has a background in mathematics, linguistics and computer science – and then a little philosophy and psychology as well.

“Most of us in cognitive science have a motley background. But, we are all interested in how thought processes work.”